During the 1910s and 1920s, artists in Germany and Austria challenged themselves to devise expressive techniques to create art that captured a deeper understanding and more genuine representation of the human experience in the midst of rapid societal, cultural, and geopolitical shifts.

The German Expressionists, with their audacious distortions, simplified angular shapes, and the employment of unconventional colors, aimed to articulate intricate emotional and psychological reactions to the shifting landscape of their era, which was marked by significant social, cultural, and political transformations in the early 20th century.

Advertisement:

Rejecting traditional societal norms, they eschewed established notions of idealized, timeless beauty and opted for bold artistic approaches that not only mirrored but also played a role in the era’s revolutionary developments.

Numerous artists were attracted to the expressive potential of printmaking. They successfully harnessed a spectrum of textures and tonal variations in their prints, ranging from the delicate, velvety lines of drypoint to the juxtaposed, sharply fractured or artistically gouged marks of woodcut.

“Allerheiligen/ All Saints Day” by Wassily Kandinsky, original color woodcut, c.1911

They also explored the granular qualities and wash-like drawing effects achievable through lithography, as well as the nuanced transitions in continuous tone made possible by aquatint.

The diverse methods of ink application and the utilization of various color inks in their prints aligned perfectly with the artists’ inclination to experiment with materials.

The Anxious Eye: German Expressionism and Its Legacy

“The Anxious Eye: German Expressionism and Its Legacy” showcases artworks that delve into four main themes: portraits and modern life, nature and spirituality, relationships and body language, and the enduring influence of German Expressionism.

This exhibition provides fresh insights stemming from our enhanced comprehension of the intricate and long-lasting effects of World War I, which concluded over a century ago in 1918. It also introduces novel approaches to expanding the traditional narratives of art history.

The exhibition will be available for public viewing at the West Building of the National Gallery of Art from February 11 to May 27, 2024. It showcases over 100 prints, drawings, illustrated books, portfolios, and two sculptures. The pieces span a period from 1908 to 2021.

All the exhibited works, including recent acquisitions and rarely displayed pieces, are sourced from the National Gallery’s permanent collection. In addition to renowned artists such as Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Käthe Kollwitz, Emil Nolde, and Egon Schiele, the display will also feature prints by lesser-known artists like Paul Gangolf, Walter Gramatté, and Otto Mueller.

Room One: Portraits and Modern Life

In the first room, visitors encounter profound portraits and self-portraits that delve into the inner thoughts and emotional states of the subjects, prioritizing these over precise realistic depictions of appearance.

These works were influenced by the emerging ideas of personality traits and states of mind developed by pioneering psychology scholars and philosophers of the early 20th century, namely Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung.

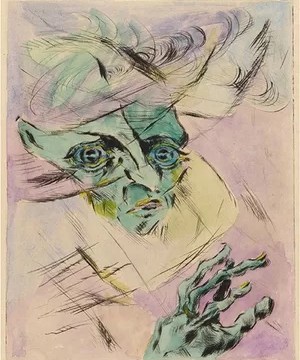

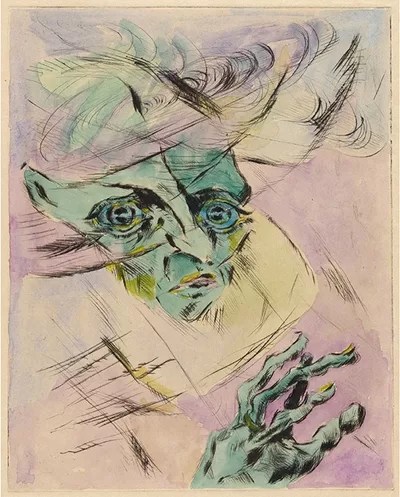

Notably, the figures in pieces such as Walter Gramatté’s 1918 self-portrait, “Die Grosse Angst” (The Great Anxiety), with its incisive diagonals, trembling lines, and contorted fingers, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s 1916 woodcut portrait “Fanny Wocke,” characterized by tight framing and gouged, carved, and scratched facial features, exemplify how artists harnessed the unique attributes of different artistic media to convey emotional intensity.

Furthermore, prints and illustrated books by Max Beckmann, Lovis Corinth, Otto Dix, Paul Gangolf, and George Grosz illuminate the emotional and political climate of the era.

These artworks capture the dynamics of modern life, the growing congestion in cities, and the ensuing feelings of isolation and anonymity.

They also depict discontent with the prevailing social order and bourgeois values, as well as the horrors of World War I.

Room two: Nature and Spirituality

The second gallery transports viewers to religious subjects and landscapes, which artists explored as a form of solace from the complexities and stresses of daily life while simultaneously questioning faith and humanity’s destructive impact on the world.

Highlights in this section include Lovis Corinth’s and Otto Mueller’s interpretations of the Old Testament tale of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, Karl Schmidt-Rotluff’s vibrant pink and green woodcut portraying rocky mountains, and Emil Nolde’s somber view of the harbor in Hamburg, Germany.

“70 Jahre Alt (70 Year Old)” by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, 1926

The exhibition’s final room delves into these concepts by examining the work of later artists who employed similar approaches in mark making, materials, and an immediate sense of engagement to respond to comparable circumstances and concerns.

Particularly noteworthy are the parallels between the challenges faced by contemporary artists today and those faced by artists of the past.

Room three: Relationships and Body Language

The German Expressionists held a profound fascination with how gestures and movement could convey a wide range of emotions such as love, fear, sorrow, and joy, as well as aspects of one’s emotional state and personality.

The diverse approaches these artists explored to represent the human body, sexuality, and interpersonal relationships take center stage in the third gallery.

Die grosse Angst Selbstportrat Kopf im Halbprofil nach rechts 1918

In Walter Gramatté’s “The Couple” (Self-Portrait with Wife) from 1922, the horizontal green band cutting across the composition symbolizes the tensions that can arise between husband and wife.

On the other hand, Käthe Kollwitz’s bronze relief, “In God’s Hands” from 1935/1936, conveys feelings of love and security, portraying a small child enveloped protectively in the arms of an adult, represented only by a pair of hands.

These artists, in contrast to conventional academic depictions of idealized nudes, embraced a variety of body types and unsettling poses.

This is evident in Egon Schiele’s “Standing Nude with Patterned Robe” from 1917, characterized by the exaggeratedly contorted and colorful surface, and Erich Heckel’s “Nude” from around 1913, where a model is awkwardly posed while kneeling on a rug.

Their sources of inspiration extended to the art of Africa and the South Pacific Islands, although these were often viewed through a biased colonial lens as “primitive” societies untouched by “civilization.”

This influence is evident in the elongated and exaggerated shapes, and the articulation of certain features, as seen in Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s lithograph “Two Women” from 1914 and his roughly hewn wooden sculpture “Head of a Woman” from 1913.

Similarly, Emil Nolde’s color lithograph, “Dancer” (Tänzerin) from 1913, exemplifies the artists’ exploration of what they perceived as “primitive” aesthetic sensibilities that expressed the vital forces of human experience through dynamic movement and exaggerated forms.

Room four: the Enduring Influence of German Expressionism

The final space in the exhibition delves into the enduring influence of German Expressionism and how contemporary artists continue to draw from its stylistic approaches to convey the heightened emotional and psychological experiences associated with pivotal societal shifts.

“Portrait of Emy” by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, 1919

A notable piece is Leonard Baskin’s “The Hydrogen Man” from 1954, featuring a transparent one-armed figure intricately crafted with a network of woodcut lines, serving as a warning about the devastating consequences of modern nuclear warfare.

In Rashid Johnson’s composition “Untitled Anxious Red” (2021), a grid of highly abstract boxes filled with “scribbled” faces captures the elevated fear of contracting a deadly disease during the COVID pandemic.

It also reflects the challenge of navigating the anxiety of being a Black man in America, particularly given the heightened tensions resulting from the death of George Floyd and the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Among the recent acquisitions by the National Gallery are Nicole Eisenman’s “Beer Garden” (2012–2017), which combines self-portraiture with various caricatured figures reminiscent of Max Beckmann’s prints in the first gallery.

Another notable work is Orit Hofshi’s “Time… thou ceaseless lackey to eternity” (2017), in which the artist stands in a landscape ravaged by war and climate change, surrounded by displaced individuals seeking refuge and a path to a brighter future.

The Anxious Eye: German Expressionism and Its Legacy

National Gallery of Art, Washington, February 11–May 27, 2024

Related stories

German Expressionism: Art Born of Self-Expression

Heinz Schulz-Neudamm: Fritz Lang’s Metropolis Iconic Poster

The Angry Penguins Movement in 1940’s & 1950’s Melbourne

Further Reading:

German and Austrian Expressionism in the United States, 1900-1939 by Edward Hagemann

Primitive Renaissance: Rethinking German Expressionism (Modern German Culture and Literature Series) by David Pan

GermanExpressionism: Art and Society by Stephanie Barron

German Expressionist Painting. by Peter Howard Selz

Haunted Screen Expressionism in the German Cinema by Lotte Eisner

Expressionism: A Revolution in German Art by Dietmar Elger

German Expressionist Woodcuts by Shane Weller

German Expressionism: Primitivism and Modernity by Jill Lloyd

The Expressionists (World of Art) by Wolf-Dieter Dube

Lulu Plays and Other Sex Tragedies (German Expressionism) by Frank Wedekind

The Ideological Crisis of Expressionism: The Literary and Artistic German War Colony in Belgium 1914-1918 by Rainer Rumold, O.K. Werckmeister

The Blue Four: Feininger, Jawlensky, Kandinsky, and Klee in the New World by Vivian Endicott Barnett

Kandinsky by Jelena Hahl-Koch

Klee and Kandinsky in Munich and at the Bauhaus by Beeke Sell Tower

Vasily Kandinsky: A Colorful Life: The Collection of the Lenbachhaus, Munich by Vivian Endicott Barnett

Wassily Kandinsky and Gabriele Munter by Annegret Hoberg, Wassily Kandinsky